Ray Tracing in One Weekend : GPU Addition

Over the week, my latest obsession has been to implement a GPU based ray tracer. Initially, I did read up on using fragment shaders, but it has its limits. So before I even started, I switched over to using compute shaders.

For anyone who is intent on implementing their own should probably give Peter Shirley’s book good read. I have closely followed it for my project and I’m just going to write about parts that cover the problems I faced when porting the logic to the compute shaders.

My final code (for the first book) can be found on GitHub

I’m going to be vague here, since everyone has their own taste in what libraries they want to use for OpenGL context creation, Window creation, or the way they write their code, etc. All opinions are personal, and my code may or may not be the most efficient or perfect code. All I can guarantee is that as far as I know, it works.

So here it goes:

0. Before starting⌗

You need Windows, or Linux – MacOS doesn’t support OpenGL past version 4.1 so you’re stuck without a compute shader.

You also need a GPU. Most work, including quite a few versions of Intel UHD integrated GPU’s. Do note however, they may be very slow, and you’ll have a lower limit on how much you can process at a time. But I have already run my code on Intel UHD Graphics 630 and it works.

Also do definitely check what GPU your program runs on. Sometimes they default to Integrated graphics despite having dedicated GPUs.

1. Output⌗

In the book, we start printing colors to a .ppm file, which allows it to be viewed later. Using OpenGL, that functionality is not really the most convenient. When you can see instant results, why not?

So the simplest way for that, is to let the compute shader output the image in a texture, and then use a simple vertex shader/ fragment shader combo to render the texture to a quad. It’s a very trivial pipeline, simply forward vertices, transform the coordinates from -1,1 to 0,1 for the texture coordinates, and map the texture onto the quad in the fragment shader.

You can save the texture to an image if you wish using a library like STB Image but I prefer to simply take screenshots.

2. Classes and Inheritance⌗

GPU is a simple device so it has no inheritance. You have to make do with structs and functions. Simple sphere struct and simple material struct.

However for material and the scatter function, you don’t need multiple structs! Just add constants/enums to specify the type of material (Lambertian, Metallic, Dielectric), albedo, and one param (

Just add a switch statement in the scatter function to get your work done. Ofcourse, this comes at its own cost - branching isn’t cheap on the GPU.

#define LAMBERTIAN 0

#define METALLIC 1

#define DIELECTRIC 2

struct Material {

vec3 albedo; // align 16 size 12 | Packed

float param; // align 4 size 4 | Together

int type;

} mat;

retval scatter(in Material mat, ...) {

switch (mat.type) {

case LAMBERTIAN: scatter_lambert(mat, ...); break;

case METALLIC: scatter_metallic(mat, ...); break;

case DIELECTRIC: scatter_dielectric(mat, ...); break;

}

}

3. Samples⌗

In a game-like setting we use iteration for passage of time. But in a still frame render we can utilize this elsewhere. I personally use this for sampling. Each iteration samples the whole scene once and then the next iteration will add (weighted average) to the color in the texture, giving you the anti-aliasing effect. However this does become an infinite process that you only stop when required.

But you can’t just start sending random sampling rays yet.

4. Random Number Generator⌗

Despite most C compilers having drand48, Compute Shaders don’t have that. So you need to write your own RNG. Now I came across this nice post by Nathan Reed, both lcg and xorshift have worked well for me, but I still stick to xorshift. And instead of using wang hash and generating a seed to only use the sequence for a few iterations, it’s much easier to use an SSBO to preserve states across different iterations. This simply makes it a RNG depth problem which xorshift handles.

5. Recursion⌗

Peter Shirley uses a recursive call to Color function to get the scattered colors. The issue with this, on a GPU, is that recursion is not allowed. Thank the gods of theoretical computer science that we know that each recursive algorithm can be converted to an iterative alternative.

In our case, we just return the attenuation from the relevant function. In my case the color function is called once from the main, and inside the color function, my code iterates with each iteration calculating a new scattered ray and multiplying the color to a variable which finally is returned from the color function. You can see it in action here. It is a little obscure. Just know that hit contains the Ray.

All you simply need to do is find your way of converting the recursion to iteration.

6. Random in Unit Sphere⌗

Sometimes my Random in Unit Sphere code iterated way too many times (enough for the GPU to kill my program), when running at full 1080p

The simple solution, which traded accuracy for safety, multiplied the generated vector with an attenuation factor. Every iteration, this variable with by multiplied by 0.99 so by basic mathematics, we can see that even the longest generated vector <1,1,1> would be multiplied to fit inside the sphere in 50-ish iterations.

Of course, normalizing the vector would work even faster, but the distribution would run even more uneven.

However a little bit of performance can be sacrificed to use the radial coordinates method.

And most of the times, at lower resolutions, you won’t ever see this issue crop up.

7. Bypassing TDR (Windows)⌗

You might not face the issue of GPU drivers killing your program on higher end cards (at least for the program in the book). But if your GPU spends too much time on your task on Windows, the GPU process will be killed and a nice amazing TDR error. So you might want/need to reduce the size of the compute. The simplest way is to reduce resolution, but that would be weaseling out of the problem.

My solution was to compute in chunks. I divided the screen space into smaller chunks and processed them one at a time. It’s simple enough to implement. The real deal is to find the right chunk size. Too big? You might just hit the GPU limit. Too small, you waste time in GPU/CPU communication etc.

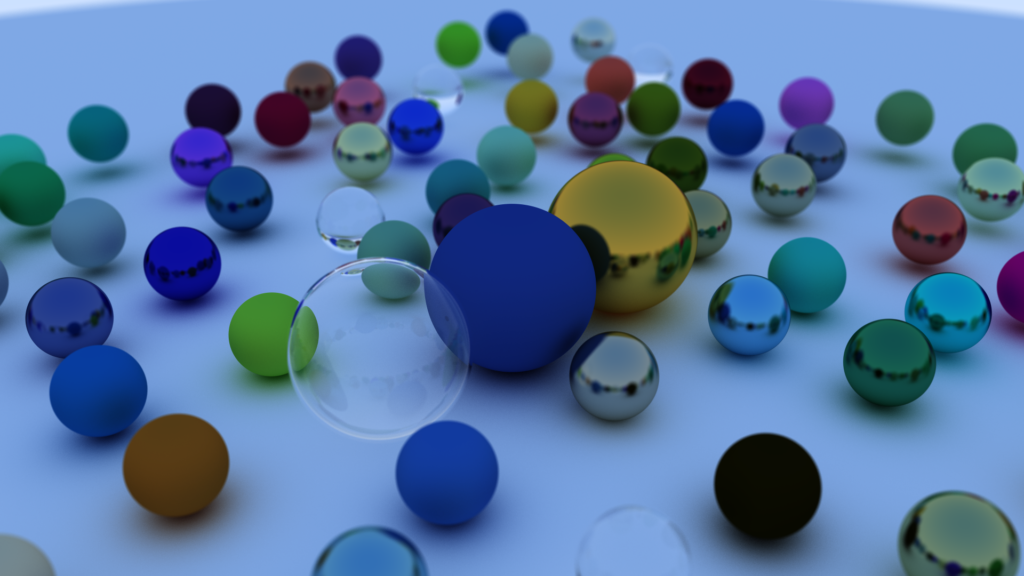

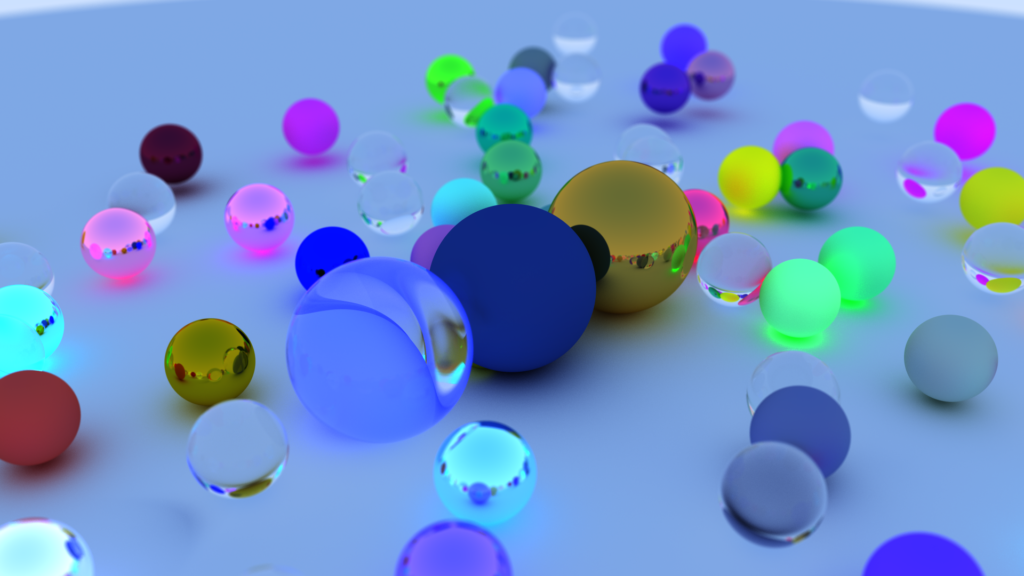

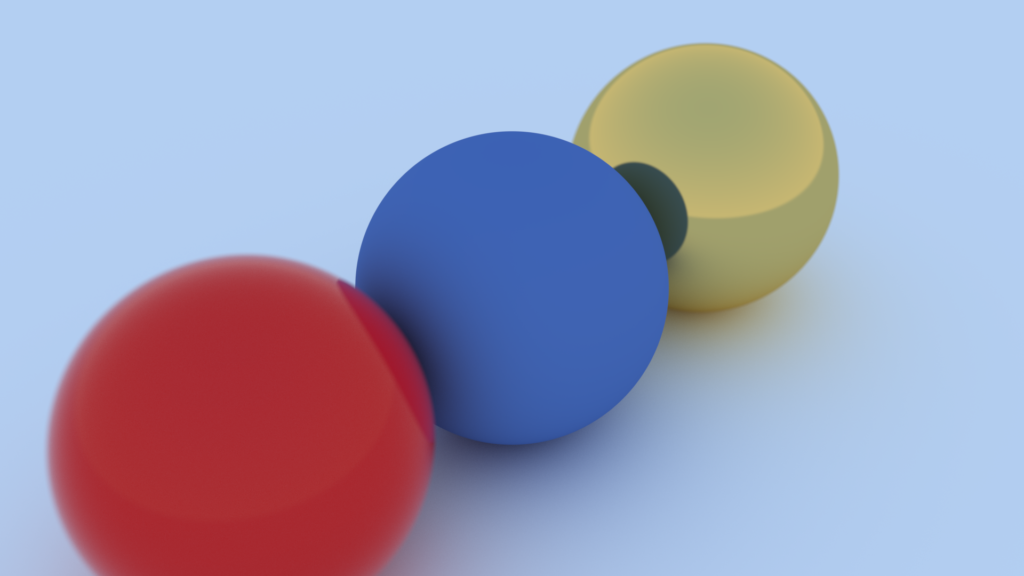

Below are some of the images from my ray-tracer. Each of them were let render for 10 minutes, although lesser could have sufficed.

The one with glowing balls was a bug where the albedo of the spheres were greater than 1.0, causing the reflected light to be amplified. Let alone energy conserving - this was producing energy. (I wish this was real: unlimited_power.exe)

The one with glowing balls was a bug where the albedo of the spheres were greater than 1.0, causing the reflected light to be amplified. Let alone energy conserving - this was producing energy. (I wish this was real: unlimited_power.exe)

That’s pretty much all the problems I faced during the project. If you find any other issues, please feel free to email me!